Serial processing is a powerful mixing technique that can produce effective and aggressive signal processing results without harshness or unwanted artifacts. In this blog, we’ll teach you how to use serial processing to make your mixes sound more polished. But first, let’s talk about what serial processing actually is.

What Is Serial Processing?

It may sound advanced, but serial processing is actually a pretty simple technique. In fact, you may already be using serial processing in your mixes without even knowing it. Serial processing is simply using more than one of the same type of plug-in or signal processor on an instrument or vocal.

For instance, instead of using one compressor to apply 10 dB of gain reduction, you would use two compressors in series to apply 5 dB of gain reduction each. The compressors don’t have to be back-to-back in the signal chain, just as long as they’re both applied to the same channel.

By splitting the work between two separate compressors, you’re able to achieve the desired amount of gain reduction with transparent results. For most plugins, splitting the work between two processors (especially compressors) tends to sound better than having one processor do all the heavy lifting.

Analog compressors, like the Universal 1176 are known for their ability to crush a vocal with up to 20dB of compression to create an edgy, controlled rock vocal sound. Plugins, however, often lose the natural character of a sound when they are overused in a similar way. Stacking compressors in series can effectively achieve a result similar to one hardware 1176.

Serial Vs Parallel Processing

For those of you who already use parallel processing in your mixes, you may be wondering about the differences between these two techniques. [For a refresher on parallel processing for vocals, check out Eli Krantzberg’s article on our blog.]

In parallel processing, you send a track to an aux channel or create a duplicate track and apply aggressive signal processing to the duplicate track. Then subtly blend the processed track in with the original to add excitement without taking away the naturalness of the original track. Alternatively, many plugins provide a wet/dry mix knob that effectively allows a processed version and the original version of the track to be blended together in a parallel manner.

Here’s the difference; with parallel processing, you hear the unprocessed track and the heavily-processed track playing at the same time. With serial processing, you can get the effects of extreme processing without the negative tonal qualities like pumping, distortion or artifacts. Each of these techniques has a unique sound and can even be utilized in the same mix. Just be careful not to over-compress your tracks!

Serial Processing In Your Mixes

Let’s take a look at some common uses of processing that you can use to help dial in the desired tone in your mixes.

I. Serial Compression

Serial compression is arguably one of the most common forms of serial processing. Serial compression is an effective tool for controlling dynamics, shaping transients, fattening up a sound, adding harmonics, and more.

As mentioned above, serial compression can be used to apply large amounts of compression without creating unwanted artifacts or distortion. However, it can also be used to simultaneously apply different types of compression to one sound.

For instance, say you have a dynamic vocal track in a busy mix. To help the vocal to sit on top of the mix, you could use a compressor with a fast attack speed to tame transient peaks, followed by a compressor with a slower attack and release to gently squeeze the track for more consistent average levels. This results in peak and RMS compression—great for a vocal.

If you’ve ever used the classic combination of an 1176 and an LA-2A, you know what I’m talking about. The 1176 has quick attack and release times to transparently catch transients, while the LA-2A levels out sustained notes with its moderate attack and long release times.

This serial technique can also be applied to other instruments, like drums. Try using a compressor with variable attack and release times to shape the transients, and a compressor with a slow attack and fast release to bring up the ambience and tone. Just remember to use the faster compressor first. [For more tips on this type of drum processing, check out Tiki Horea’s tips on drum compression.]

Serial compression can also be used to fatten up your sound or add harmonics to help an instrument cut through the mix.

For instance, many engineers like running tracks through analog compressors in bypass mode—just to capture the tone of the circuit components. Of course, since this compressor isn’t actually applying any gain reduction, you’ll need another unit to do the gain reduction.

Many engineers also pair different types of compressors together for their tonal qualities. The 1176 + LA-2A setup listed above combines the gritty tones of a FET compressor with the warmth of a tube-and-transformer-based optical compressor.

It’s also common to combine fast-acting, precise VCA compressors with slow, musical compressors like the Manley Variable Mu® or the legendary Fairchild 670. This approach combines fast and accurate gain reduction with colorful tube saturation.

In a mastering setting, a slower compressor, like the Manley Variable Mu, would be used to “glue” and harmonically enhance a mix and then a subsequent transparent limiter would catch the peaks and set the overall loudness.

II. Serial De-Essing

Like serial compression, serial de-essing uses multiple de-essers to apply gain reduction. This approach works great for vocal or cymbal recordings with technical problems, as you can apply massive amounts of gain reduction without sounding obvious or creating a “lisping” effect.

You can also use this technique to pinpoint multiple problem frequencies in a single voice. For instance, if a vocal has sibilance around 5 kHz and also around 8 kHz but a wideband de-esser causes the vocal to sound weak or thin, serial de-essing with different sidechain frequencies can discretely solve the problem.

III. Serial EQ

Serial EQ is an excellent tool for making surgical EQ adjustments to tracks. When working with instruments with multiple resonant points like guitars or drums, you can quickly run out of EQ bands trying to target each problem frequency.

That’s where serial EQ comes in. Simply add another instance of your favorite equalizer and continue carving like it’s Thanksgiving Day. Often, one EQ before a compressor and one after the compressor provides effective cleanup (pre compressors) and tone-shaping (post).

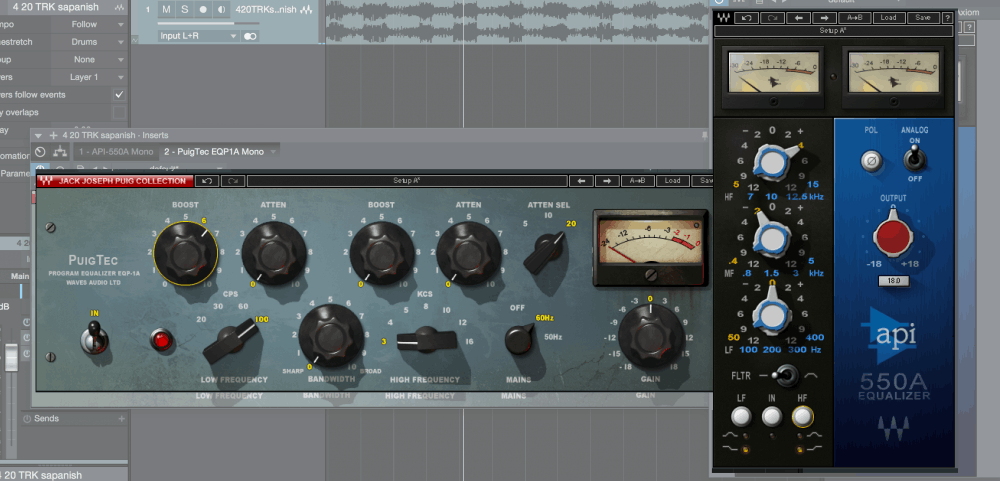

Additionally, serial EQ can be used to combine colors from different EQ circuits. Many analog EQs are revered for their unique tones, like the Neve 1073, the SSL G-Channel, and the API 550. Using serial EQs allows you to pick and choose different units for different sounds. For instance, you could use the Neve EQ to boost the low-mids, the SSL to boost the mids, and the API to boost the highs.

IV. Bus Processing

Technically, subgroup or bus processing can be another form of serial processing when you have already applied signal processing on the individual channels. Think of this like salting a burger before cooking it and then adding more salt after it’s been cooked and loaded with condiments.

One of the most common examples of this would be compressing your individual drum tracks, then adding another compressor on the drum bus to glue all the drums together. Another example would be equalizing multiple lead vocal tracks and then adding an EQ to the vocal bus. You can even take things a step further by applying processing on the entire mix bus.

It’s not uncommon to see a track with two compressors on the channel strip, a compressor on the instrument bus, and a compressor on the mix bus. Even with modest settings, that could easily result in 10dB or more of gain reduction.

A Little History

Anyone who has studied the Beatles’ recording techniques knows that during projects like Sgt. Peppers, they were recording to 4-track tape machines. After filling up three or four tracks, the tracks would be sub-mixed together and printed to a single track on another 4-track machine, usually through a Fairchild or Altec compressor with a slight amount of gain reduction. After many such ‘bounces’ the final tracks had been run several times through similar compression setups. This may sound like a lot of processing, but who can argue with the sound of those records!

Remember, serial processing is about achieving effective and often extreme results using subtle settings. Experiment, but careful not to over-do it!