We spend our lives hovering between the threshold of pain and the threshold of human hearing. Music has the power to seduce us into flirting with the upper thresholds of our biological limits. Anyone that has been to a live concert event in just about any popular genre has experienced potentially short-term hearing impairment and potentially long-term damage that may not be immediately realised. Just about every book that deals with the fundamentals of audio has a section about hearing and safe practices. This article explores some of those ideas.

Hearing vs. Listening

The distinction between hearing and listening is not so obvious to those outside the audio or music profession. Hearing is simply the ability to perceive sound, while listening is a more active process that requires focused attention. The difference can be illustrated in by comparing two simple scenarios. If someone were to clap unexpectedly behind your head, you might flinch as an automatic reaction. This could be related to a survival instinct. In the opposite extreme, consider the listening skills of an experienced audio engineer. Mixing or mastering requires hyper-focussed attention to detail for extended periods of time. A person might be able to adequately hear without any listening skills, but the audio engineer relies heavily on his or her ability to hear a wide range of frequency and changes in amplitude in order to do their job.

“Mixing or mastering requires hyper-focussed attention to detail for extended periods of time.”

Types of Hearing Loss and Exposure Limits

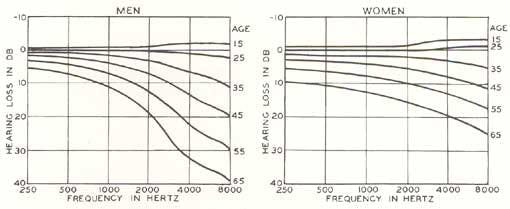

While we are taught that the range of human hearing is 20Hz to 20kHz, this perceptual ability begins to decrease particularly in the higher frequencies around our late twenties, regardless of what protective actions we may take. Failure to take precautionary steps to protect our hearing will accelerate the process of hearing loss over our lifetime.

Acoustic trauma can be caused by a sudden loud noise in excess of 140dB and can cause permanent hearing loss.

Prolonged exposure to elevated levels of sound can change our ability to perceive amplitude. A phenomenon called temporary threshold shift occurs from exposure to loud sounds for an extended period. Things will sound muffled for a while afterwards but will ultimately return to normal. However, in a talk at the AES Conference (2018) Sharon Kujawa explained that, “…a more insidious process is occurring that doesn’t kill hair cells, but instead, permanently interrupts their communication (synapses) with cochlear neurons. This cochlear synaptic loss can be dramatic, even when thresholds return to normal after exposure, where it has been called ‘hidden hearing loss.’ The injury changes the way ears and hearing age…” (Kujawa)

“Prolonged exposure to loud sounds can bring on tinnitus, a ringing, whistling, or buzzing in ears”. (Alten 20) This may be a danger sign that a permanent threshold shift has occurred or will occur.

Corey explains that the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Administration (NIOSH) recommends the following exposure limits as being relatively safe: (Corey 21)

- 82dBA up to 16 hours per day

- 85dBA up to 8 hours per day

- 88dBA up to 4 hours per day

- 91dBA up to 2 hours per day

- 94dBA up to 1 hours per day

- 97dBA up to 30 minutes per day

- 100dBA up to 15 minutes per day

According to these guidelines, as the level increases by 3dBA, the allowable exposure is reduced by half.

Human Perception

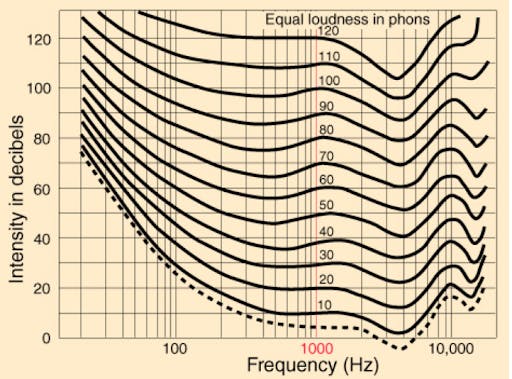

In addition to decreases in hearing ability caused on abuse, humans have a naturally higher sensitivity to midrange frequencies (1Hz – 5kHz), something that has been attributed to an evolutionary response and the fact that resonances in the ear canal correspond to the intelligibility of human speech. As described by the Fletcher-Munson Equal Loudness Contours (Thompson 210-211), at low volume levels, our ability to perceive low and high frequencies is diminished relative to the mid-range. This disparity is decreased as levels increase. But cranking things up and mixing at 120dB is clearly not the solution, as emphasized by the NIOSH recommendations above. Besides the potential for long-term damage, it would be impossible to achieve a mix that would translate to a variety of listening levels if you were to mix everything that loud. Likewise, mixing at extremely low levels would cause you to overcompensate for perceived low end and high frequencies. For more information on amplitude and loudness check out my article on The Pro Audio Files (Mantione).

“…if you must raise your voice to be heard, then you’re monitoring too loudly”

Listening Levels and Best Practices

So what are safe levels in terms of listening for extended periods of time? Huber suggests monitor sound pressure levels of 85dB with 15 minute breaks of quiet time every few hours. (Huber 66) Some engineers suggest mixing at even lower levels such as 65dB to 75dB, and then periodically auditioning the mix at various levels to insure that it will translate well. Huber states that, “…if you must raise your voice to be heard, then you’re monitoring too loudly” (Huber 66). Moylan believes that listening levels should range from 85 dB to 90dB with peaks being at 90dB and that engineers should maintain a consistent level throughout the project (Moylan 305).

Hearing Protection

Outside the studio you will have far less control over levels. Musicians and live sound engineers are routinely exposed to dangerous sound levels. There are several choices of ear protection available from the inexpensive and readily available foam ear plugs to custom molded plugs to musician ear plugs designed to attenuate frequencies evenly across the spectrum. Anyone exposed to extreme volume levels on a regular basis or even occasionally is well-advised to employ some sort of protection. Caution should be used when using headphones or IEM’s (in-ear-monitors) for extended periods of time for all the reasons mentioned above. Lastly, getting your hearing checked periodically by an audiologist is advisable. While hearing loss may not be reversible, monitoring objective measurements of your hearing over time may motivate you to consider protective actions more seriously.

“While hearing loss may not be reversible, monitoring objective measurements of your hearing over time may motivate you to consider protective actions more seriously.”

Conclusion

There are limits to everything and in particular our human biology. Failure to recognize this as a matter of fact invites irreversible damage to our sensory capabilities on top of the natural degradation that results from the aging process. We are not invincible when it comes to the natural and manmade stimuli that we are bombarded with on a daily basis. Musicians and audio professionals are inextricably dependent on the ability to hear. But beyond this instinctual sense is the capability to listen and perceive the finest detail and subtle changes in timbre and intensity. Even at appropriate or safe levels an engineer can lose perspective and the ability to make good decisions when listening over extended periods of time. It is crucial to take frequent breaks, not only to avoid damage to our delicate hearing mechanism, but to preserve our sense of artistic judgement, which is arguably equally as fragile.

You can follow the author on Twitter: @PMantione and Instagram: philipmantione

Sources

Alten, Stanley R. Audio in Media. Wadsworth Pub. Co., 1999.

Corey, Jason. Audio Production and Critical Listening: Technical Ear Training. Focal Press, 2013.

Everest, Alton F., and Ken C. Pohlmann. Master Handbook of Acoustics. McGraw-Hill, 2009.

Everest, F. Alton. Critical Listening Skills for Audio Professionals. Thomson Course Technology, 2007.

Howard, David M., et al. Acoustics and Psychoacoustics. Focal Press, 2013.

Huber, David Miles., and Robert E. Runstein. Modern Recording Techniques. Focal Press, Taylor & Francis Group, 2014.

Kujawa, S., PhD. (n.d.). Invited Talk: Sharon Kujawa, PhD (Harvard Medical School). Retrieved September 19, 2018, from http://www.aes.org/conferences/2018/hearing/program.cfm

Mantione, P. (2018, July 03). The Fundamentals of Amplitude and Loudness. Retrieved September 19, 2018, from https://theproaudiofiles.com/amplitude-and-loudness/

Moylan, William, and William Moylan. Understanding and Crafting the Mix the Art of Recording. Elsevier/Focal Press, 2013.

Russell, R. (n.d.). Listening and Hearing. Retrieved September 19, 2018, from http://www.roger-russell.com/hearing/hearing.htm

Thompson, Daniel M. Understanding Audio: Getting the Most out of Your Project or Professional Recording Studio. Berklee Press, 2005.

Winer, Ethan. The Audio Expert: Everything You Need to Know about Audio. Focal Press, 2013.