Have you ever listened to one of your good-sounding stereo mixes in mono and noticed that some elements become thinner, weaker, or maybe they’re entirely gone? If so, your mix most likely has some phase cancellation issues. Is it relevant to listen to or check your mixes in mono in today’s world? Of course, it is.

Sound systems in clubs and pubs are often mono, as are many subwoofer systems in venues. Sound systems in malls, grocery stores, and other public spaces may be mono. Essentially, any speaker setup where the speakers are either too close together or too far apart for the listener to perceive stereo sound should be considered a mono playback system.

Mixing to ensure mono-compatibility cannot be achieved with a blanket approach. Mix elements should sound similarly balanced when played back in stereo or mono, and skilled mixers are alert for the problems that folding a stereo mix to mono may create. Let’s take a look at what causes phase issues and learn how to avoid recording sounds that can cause phase problems. This will help us mix without worrying about phase issues should our mix fold down to mono.

What is phase?

“Phase” refers to the position of a sound wave in time, measured in degrees. The animation below shows how a circle and a sine wave can simultaneously represent the phase of a signal by displaying the same signal’s amplitude and angular frequency over time.

As the green dot at the head of the signal moves, its position can be described in degrees. The 360 degrees of phase angle shown on the circle match the phase of the sine wave at the same point in time. When the signal reaches the highest amplitude on the circle and the sine wave, its rotation has covered 90˚.

Phase is a relative measurement, meaning the phase of audio signals really only matters to us when two of the same, or very similar waveforms combine either acoustically or during a mix. A single sound will not be perceived by a listener as having a correct polarity. When one sound source is captured by two microphones the resulting output consists of two signals, and the phase relationship between the two microphone signals is significant. Moving the position of one microphone relative to the other will result in an audibly different blend when the two signals are mixed together.

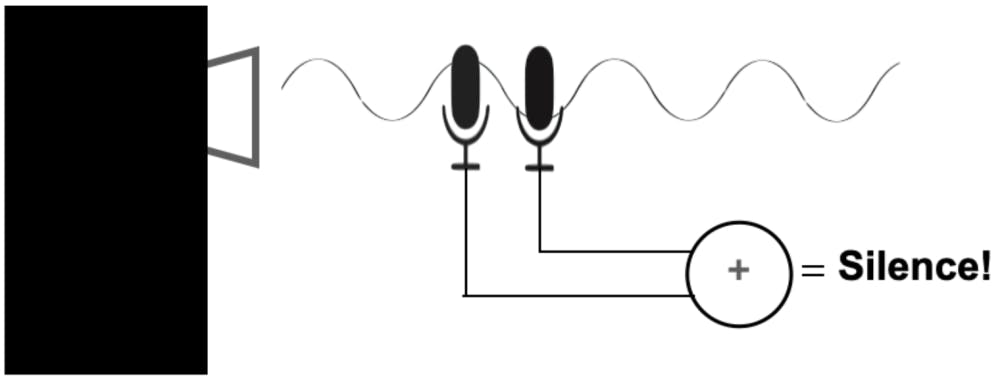

Let’s take the example of a sine wave playing from a single speaker and being picked up by two microphones placed at slightly different distances from the speaker. The first microphone picks up the waveform at its highest amplitude and the second microphone picks it up at its lowest amplitude. The two microphones’ signals are 180˚out of phase with each other. If these signals are added together, the result would be silence.

Polarity or Phase?

Ø

You’ve seen this symbol on switches and buttons on all kinds of analog gear and plugins. People often say it “flips the phase of a signal.” To be precise, you should say that the switch reverses the polarity of the signal. A polarity reverse makes a peak into a valley, whilst keeping the timing intact. In contrast, phase shift makes a peak into a valley by sliding the timing of one waveform with respect to the other with atime delay. The GIF below, shows two identical waveforms moving from in-phase to 180˚ out of phase with each other. On the phasor representation, you can see how many degrees one wave moves relative to the other.

Comb filtering and detecting phase issues

We know that pure sine waves mixed together with opposite polarities will cancel each other out. When two or more real-life musical signals with different phase relationships are combined, the result is audible frequency interference, called comb filtering.The resulting frequency response looks similar to a comb, with regularly spaced peaks and valleys. This can be the result of multiple microphones picking up a single sound source or when processing an audio signal with delay effects.

How to listen for comb filtering

It is important to listen for comb filtering cause by phase issues. First, pay attention to any stereo sounds that don’t have a focused center image. This may be caused by phase differences between the left and right channels. Second, if a sound seems to come from outside your speakers or from behind you, there may be phase problems. Third, if you find low-frequency instruments sound weak even when you boost their low frequencies, there may be phase problems. Fourth, if you listen to a stereo mix in mono and some sounds become much lower in volume or disappear completely, there are phase problems.

Phase problems in stereo signals and mixes may be less apparent in headphones than on speakers, so always check a headphone mix on speakers. Even laptop speakers can reveal phase problems that you might not hear in headphones. Of course, you will not be able to properly detect these issues if your speakers are not properly set up and wired in polarity with each other.

When and how do Phase problems occur?

Phase problems can occur during recording, mixing, and even mastering, so it’s important to be aware of the potential problems all along the way. Here are some times to really pay attention to phase issues:

When recording with more than 1 mic or signal path to record a source.

- Drums recorded with multiple mics are a common source of phase problems since mics placed all over will pick up the same sounds.

- Similarly, acoustic guitars, guitar cabs, pianos, and other instruments that are recorded with more than one mic are liable to have phase issues.

- Electric guitars, bass guitars, or any instrument recorded through both a DI and a microphone are at risk.

The issue in all these cases is the timing difference between the sound arriving at one mic or DI, compared to the other mic(s). This occurs because sound takes more time to travel to the furthest mic than it does to the closest one. Similarly, electrical signals travel faster than sound in the air, so the DI signal will be slightly ahead of the microphone signal. The time difference between microphones amounts to 1.13 milliseconds per foot (30 cm), and a difference of fewer than 0.04 milliseconds (1 cm) can cause an audible phase shift.

- When using drum samples

Whether you’re reinforcing live recorded drums, or creating your own kick or snare by layering samples, you run the risk of creating phase conflicts. The waveforms of the sounds must have similarly timed peaks and valleys or the mix of the sounds will become weak, with little low end.

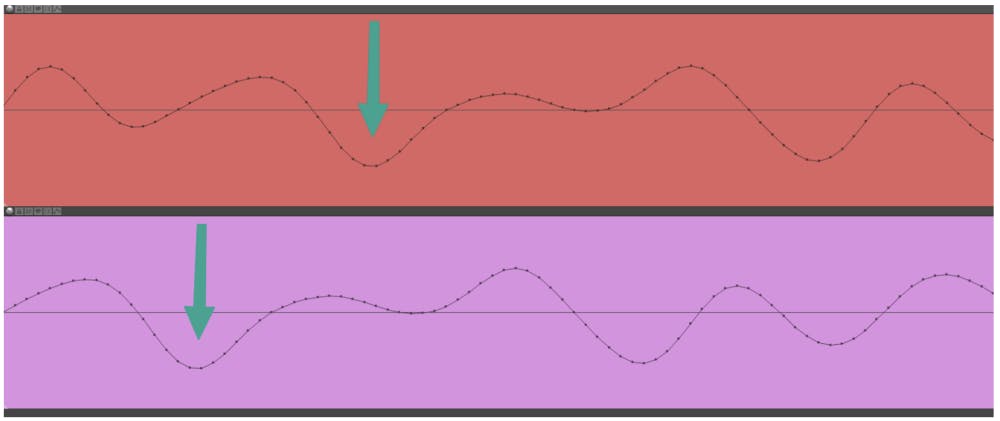

Two tracks showing the top and bottom mic for a live recorded snare drum. The top mic and bottom mic waveforms line up very well ensuring proper phase alignment. If your recorded top and bottom snare mics don’t line up like this, invert the polarity or slide the bottom snare track to better line up with the top track.

- Stereo synths

If the stereo synths in your mix sound wider than the left and right speakers, pan the two tracks center to listen to them in mono. If they sound weak, that patch probably uses phase manipulation to achieve its impressive width, which will lead to problems when collapsed into mono. For this sound, you may wish to use only one side of the signal in your mix. Sometimes panned mono signals actually fit better into a mix with a lot of wide stereo elements.

Stereo bass sounds are risky because low frequencies are destroyed by phase issues. As a general guideline, elements that have a lot of low-end content should be mono. Think kick drum, bass guitar, and synth bass tracks.

- Parallel processing

Parallel processing combines a sound with a highly processed copy of itself. If the parallel track processing affects the phase of the source in just the wrong way, you’ll end up with a crippled result. Always audition the parallel track in polarity and with reversed polarity to hear which version makes for a better result.

This holds true for top and bottom snare mics and DI and miked guitar or bass signals. Anytime two signals with mostly the same content are combined, be sure to check for polarity or phase problems.

- Stereo Imaging and Widener plugins

This sort of plugin uses psychoacoustic processing to enhance the stereo width of a track. Many try to maintain mono-compatibility, but some can cause phase problems that hurt the mono version of the mix.

- Issues inherent in the mix

Low-frequency content in a mix contains long waveforms that can interact with each other. Once a mix is coming together I find it useful to audition the bass with normal and flipped polarity to see which version sits in the mix better. You can do the same to the kick drum and even the lead vocal (one instrument at a time) to see if inverting the polarity of those signals helps the tracks fit better in the mix.

Visualizing Phase Problems

Always check your work by listening in mono, but meters can alert you to a possible phase problem. Vectorscopes and phase coherence meters provide visual feedback regarding how much in-phase and out-of-phase content a track or mix contains. Reading a phase meter takes a bit of practice, but is worth the effort. Popular vectorscopes are often part of stereo imager plugins and iZotope, Audec, and Voxengo make popular meter plugins with free options.

How to prevent phase issues

Getting the tracks right at the source, while recording, is the ideal scenario.

When recording, make sure you check the phase relationship of the mics for multitracked instruments. One easy method can be done while the musician plays. Monitor two mics in mono and flip the polarity of one mic. Adjust the mic positions until the two tracks cancel each other out as much as possible. Once the sound is horribly thin and comb filtered, undo the polarity flip, and voila! Awesomely in-phase tracks.

Stereo recordings done with coincident (X-Y) pairs provide excellent mono compatibility and a natural but somewhat narrow stereo field. Small diaphragm condensers work well for X-Y configurations because they fit on a single mic stand with a stereo bar and their small form factor allows for very precise alignment. In contrast, A spaced pair of mics can yield a larger-than-life stereo field with less mono-compatibility.

When recording drum overheads with a spaced pair, it’s very important that both mics are placed at an equal distance from the center of the snare. Place the tip of a cable at the center of the snare and bring the length of the cable to the tip of one microphone. Now adjust the second mic so that it is the same distance to the center of the snare drum.

How to fix phase issues

Phase issues can be fixed in the mix using manual or automatic techniques.

- Manually move the waveforms

If inverting the polarity doesn’t fix the problem the tracks are probably less than 180° out of phase. Zoom in to see the waveform at the sample level and grab the track that happens later in time. Move it forward until its peaks are as closely aligned as possible with the other track’s peaks. This movement can be done while listening and at the same time watching a phase correlation meter. However, be wary of moving room mics or overhead mics to try to align their waveforms with close mics as the movement might remove the spaciousness of the natural recording. On the other hand, this effect may be interesting in some situations.

- Micro-delay plugins

Tools like Waves InPhase and Little Labs IBP let you adjust the phase of a track by adjusting its timing, phase, or polarity. These plugins have plenty of other features to help with the process as well.

- Auto-align plugin

SoundRadix Auto-Align is the king of auto-alignment plugins. The plugin can compare any track(s) to a reference track and automatically suggest the best alignment. The user can choose from several suggested alignments to decide what sounds best. Auto-Align Post can time-align two microphones that move relative to each other during recording, like when an actor’s boom mic and lavalier are mixed together.

- Don’t fix phase issues

You don’t have to fix phase issues if they don’t sound bad. Some of them even make your mix sound better! For example, guitar cabinets are often multi-miked so mics can be blended to create comb filtering that adds life and dimension to the instrument’s tone. By adjusting the mix between the two mics, you can create a sound that cuts through a busy mix.

A word of warning: Some slight transient smearing and a tiny bit of comb filtering happen in nature, and fixing every possible phase discrepancy can render your mix unnatural. The transient smearing that occurs naturally when multitracking drums and guitar amps add depth and cohesion to the sound.

Conclusion

Phase incoherency is bad, except when it isn’t. Be wary of phase issues that hurt the mono version of a stereo mix, but also learn when to use phase differences to your advantage.

Have fun and treat your clients right!