The holy grail of mixing is creating mixes that sound great when played back on different systems in different environments. Mixes that do not translate well invariably suffer from problems in the low end of the frequency spectrum. In popular music genres like rock, pop, and country, the quality of the bottom usually comes down to two elements of your mix: 1. The bass. 2. The bass drum. These guys need to solidly blend together, and at the same time, stay out of each other’s way. How can we give each of these instruments punch and clarity and have them work well together?

Clear The Way

The first thing to consider is keeping other instruments out of their way. Many instruments, like electric guitar, organ, and keyboards, generate sub-harmonics that extend below their fundamental frequencies. EQ’ing out some low frequencies on these instruments helps leave room in the mix for the instruments that need lows the most. Bass, and bass (kick) drum. Be careful, though, not to filter out too much low end on other instruments, or they can become thin and weak. Low-cut EQs, either as high-pass filters or shelving EQs, are useful for this.

Visualize the Roots

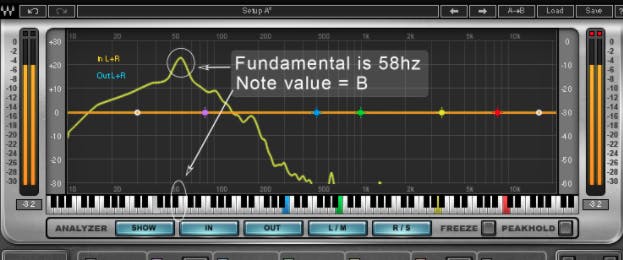

Since the kick and bass generally occupy overlapping areas of the frequency spectrum, EQs can be used to bring out their fundamental tones, which lie in slightly different ranges. Focusing the kick drum in the 40 – 70 Hz range, and the bass in the 70 – 200hz range is generally a good starting point. A spectrum analyzer (part of many EQs) can help you visualize where the energy of each instrument is most focused for your particular mix. Focus on each instrument and watch the analyzer (and listen!) to find their strongest fundamental frequencies. You may even find that the bass fundamental changes between different sections of a song.

Simple bell-shaped EQ dips and boosts work fine but may not always yield the best result. A high pass filter with a gentle slope and slight resonant peak at the cutoff point will boost either the bass or the kick drum right where it’s needed, while gradually attenuating the lower frequencies. Some EQs create this shape with one band, but you can also create this shape with a high pass filter and a bell-shaped boost playing against each other.

The Pultec EQ Trick

Simply boosting and cutting frequencies is only a starting point. Another excellent way to give one low-end element focus while leaving space for other sounds is by using the Pultec EQ Trick. The Pultec EQP-1A (and its many emulations) has a low-frequency section with separate gain knobs for boosting and attenuating the same frequency. The boost and cut, however, have slightly different curves and different amounts of gain, so boosting and cutting simultaneously can fill out the low bass while carving out a nice notch, centered at the corner frequency. The resulting curve leaves space for other instruments in the upper-bass range. Most DAWs and third-party plug-in developers offer Pultec emulations for just this application.

Sidechain Compression

Compression is another processing tool that helps low-frequency instruments stand out in a mix. For the bass drum, the right compression can add weight and presence. For bass, it can add a nice gritty edge to the attack and smooth out the sustain. In rock, pop, and country music, the kick drum and bass parts often intersect rhythmically—sometimes they play together, and sometimes they don’t. A tried-and-true technique to help these instruments play well together is sidechain compression.

Set up a sidechain compressor by first inserting a compressor on the bass track. Normally, a compressor reacts to the signal playing through it, but with sidechain compression, the compressor looks at a separate trigger signal, or side-chain input, to tell it when to compress. We can bus the kick drum signal into the bass compressor’s side-chain input—usually done via a send. The compressor on the bass will then react to the kick drum signal rather than the bass. The result is that when the kick drum plays at the same time as the bass, the kick triggers the compressor and the bass is compressed (dipped) out of the way of the kick drum. The compressor remains inactive when the kick drum is not playing, leaving the bass uncompressed. During sidechain compression, just as with regular compression, the bass level will be compressed as defined by the compressor’s threshold, ratio, attack, and release settings.

Dynamic EQ and Multiband Compression

While dynamic EQ and multiband compression are different technologies with slightly different parameters, both devices can solve similar problems—with slightly different results. Multiband compressors have been around longer, so are more familiar, but dynamic EQs tend to be more flexible and tend to have less coloration. The two main drawbacks to multiband compressors are: first, they need to split the audio into discrete frequency bands, and this splitting and recombining often cause coloration, and second the bands can’t overlap and shape the way EQ bands do. Let’s take a look at these two processors.

Multiband compressors allow you to select one or more frequency ranges and apply compression or expansion to only that band when the frequencies in that band become too loud or soft. For instance, a vocal that gets boomy on only a few phrases could benefit from a multiband compressor set to compress the low-mids when they become too prominent. A de-esser can be thought of as simply a multiband compressor that only compresses high frequencies. Some multiband compressors even provide sidechain/key inputs that allow a specific frequency band to be sidechained to another instrument. Think about only ducking the subs in a bass guitar when the kick hits, instead of ducking the entire bass sound.

Dynamic equalizers combine the precision of a parametric equalizer, with the threshold, sidechain control, and attack/release ballistics of a compressor or upward expander. Dynamic EQs allows you to position EQ dips or boosts where you need them, and then introduces a variable gain component based on the energy of the frequency content of the signal at each EQ point.

Dynamic EQs work to normalize the level of energy in each band of the frequency spectrum. In other words, the EQ reacts as the frequency content of a sound changes. The result is that an EQ band will dip or boost from its static setting based on the band’s threshold. For example, you can retain the natural accents in the bass part, but dip only the low E notes (41.2Hz) whenever they are played too loudly. Or, the EQ can boost certain weak bass notes while leaving the louder ones alone.

Many dynamic EQs also include a side-chain function, so you can set up a static EQ to boost your bass, but have a specific band dip slightly when the kick drum hits along with the bass.

Glue the Low End

In addition to working individually on bass instruments, there are ways of tightening up the bottom end of the mix as a whole. Multiband compression on a mix bus, or applied during mastering, is an excellent way of evening out the energy in a specific frequency range. Try this: Set the crossover points to restrict the lowest compressor band to below 100 Hz. Set the threshold and ratio so that a few dB of gain reduction is happening during the loud sections. Make sure not to use extremely quick attack or release times to avoid distortion. This type of frequency-specific compression can create evenness and a smooth quality to the low end.

Add Some Density

There are several specialized plug-ins that can generate harmonic content and add excitement and intensity, particularly in the low register. Vitamin from Waves is a multi-band harmonic enhancer that can instantly warm up the lows on almost any mix.

Ozone 9 from iZotope includes several mastering modules designed for low register enhancement. Low End Focus and the multi-band Exciter are both tools to add subtle warmth and focus to the bottom and help glue the mix together.

Don’t Overdo It

A great bottom end may be what separates the pros from the amateurs, but remember not to over-process your mixes. Too much of a good thing quickly becomes a bad thing when used in excess. In addition to various audio processors and a good spectrum analyzer, you always need monitors that are well-calibrated and tuned to your room. Quality monitoring is the best insurance against muddy or weak low frequencies in your mixes and masters. As mixers, we need to be able to trust what we hear, above all else.

Go ahead and rock the low end on your mixes with confidence!

More information on these topics:

Pro Mastering: Dynamic EQ and Multiband Compression