The obvious purpose of compressing vocals, or any other instrument, is to reduce the dynamic range of a particular track. With less distance (dynamic range) between the quiet and loud parts, the entire vocal can be brought up in level without clipping. Compression allows the vocals to sit more prominently in the mix and helps it to stand out. Reducing the dynamic range also allows us to hear the low-level details since their volume has been increased relative to the loud parts.

The de facto use of compression, though, yields effects beyond simple dynamic control. Compression obviously evens out the dynamics of a performance so peaks don’t jump out and quieter bits are not lost, but it can also add excitement and emphasis to a track in a way that gives it urgency and commands attention within a mix. Compression can shape transients and modify sustain, affecting the sense of an instrument’s timing within a groove. Perhaps most importantly, certain compressors change the timbre and dimensionality of a track by introducing subtle harmonic saturation.

In this article, we’ll look specifically at ways of using compression on vocals to create anything from smooth, transparent, and natural-sounding results to vibey, energetic, and colorful tracks. If you are not already familiar with the basics of compression and its parameters, you can read up on them in our article “How to Hear Compression,” by Tiki Horea.

Each type of compressor uses specific electronic components that result in unique tonal qualities. Compressors are also non-linear processors, meaning they process and color audio differently depending on the input level, threshold, ratio and even the frequency content of the audio signal. Therefore, besides dynamic processing, each compressor imparts its own unique color and distortion artifacts onto the audio that passes through it. These effects on the tone, timing, and energy of vocals are the real reasons that certain compressors have become such revered production tools.

Smooth & Clean

For natural and transparent vocal compression, conventional wisdom is to set a medium attack time and a medium to slow release time, so that the compression doesn’t draw attention to itself. Set the ratio to a modest value (somewhere in the 4:1 ballpark and adjust the threshold so the compressor is triggering a few dB of gain reduction. You are on your way to safe and effective vocal compression.

Pushing the attack to a very quick setting can effectively smooth out the transients of a particularly “spitty” or percussive vocal track while slowing the attack will let more of the consonants through before the compressor clamps down. You can now imagine how a particular attack and release setting can adjust the aggressiveness or smoothness of a particular vocal performance.

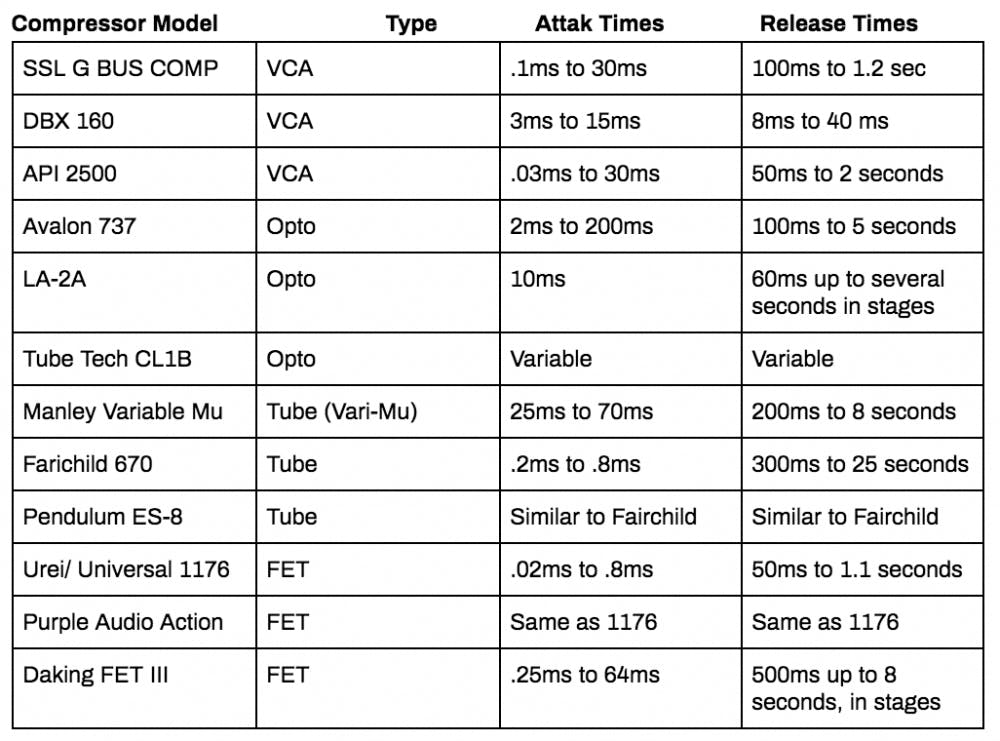

Compressors come in four basic types, based on the electronic circuits that they contain, and how they function. Let’s take a look at the four main compressor types.

1. Flexible VCAs

Voltage Controlled Amplifier type compressors are perhaps the most common and generally the most surgical. Attack, release, ratio, threshold, knee, and makeup gain are all user-definable and have wide operating ranges. Their flexible attack and release settings make them an excellent choice for unobtrusive vocal compression. VCA compressors can gently control dynamics or they can clamp down more aggressively when necessary. Bring up the makeup gain, and you’ve more than likely got a beautiful big vocal sound that will fit nicely in most mixes.

VCA compressors typically don’t color the audio and remain fairly clean and transparent even with maximum compression. The dBX 160 and 165a and SSL compressors are some of the most familiar hardware VCA compressors. See the table at the end for more descriptions of VCA compressors.

2. Add Some Optical MOJO

Optical compressors use photocells, called optos, for their detector circuit, which is the brain of the compressor. The optical device controls the attack and release times so the user may not have any controls for these parameters. Optos typically have a moderate attack time (~10ms) along with a slow release time, allowing you to push the gain reduction hard without many artifacts.

The LA2A is the classic optical compressor and it employs tubes and transformers that impart their signature flavor of harmonic color and distortion. For less colored optical compression, the LA3a and Summit TLA100 are studio favorites. There are many software emulations of these and they all sound excellent—especially on vocals. You can push them to 5-7 dB of gain reduction, add some makeup gain, and they will impart a larger than life quality to your vocal. Gain reduction and output level are the main user controls on opto compressors, making them simple to operate.

3. A Touch Of Tube Magic

The Fairchild 670 stereo tube compressor (and its mono sibling, the 660) is another excellent choice for vocal compression. This type of compressor is known generically as a tube compressor and Manley refers to their version as the Variable Mu® compressor. Tube compressors work differently than VCA and Optical compressors, relying on a tube to control the ratio and action of the compressor. The Fairchild has a very fast attack, in the range of half a millisecond, along with a slow to very slow release time. Notably, tube compressors don’t kick in aggressively when a signal is detected. Instead, their ratio automatically increases from around 2:1 up to limiting as the input level and the corresponding amount of gain reduction increases. This variable ratio results in a transparent “soft knee” type of behavior.

Fairchild 660 and 670 attack and release times are adjusted using a single Time Constant knob. Each of the six selectable time constant settings provides a specific combination of a quick attack time and either a moderately-slow or program-dependent release time.

More important than gain reduction, Fairchild compressors impart their unique sonic signature onto whatever you put through them. This color and harmonic richness is no doubt the result of the hardware unit’s 20 valves and 14 transformers! Simply running a vocal through it while barely triggering the gain reduction enhances the vocal’s clarity and presence and imparts a smooth and warm character. Clamping down hard imparts a beautiful, lush sound that generally flatters vocals. The Beatles famously used modified Altec 436B tube compressors (renamed the EMI RS124) and Fairchild compressors on most of their vocal and bass tracks.

4. Grab Me Tight with Transistors

Another class of compressors, suitable for slightly more aggressive treatment of vocals, is the FET (field effect transistor) based compressor. Unlike the smooth VCA compressors, which typically react to the RMS (average) level of track, the FET compressor reacts to the shorter peak levels of an audio track.

Geekiness aside, the critical thing to know is that the attack times on FET compressors are extremely fast, well below one millisecond, and FET circuits tend to brighten the tone and add extra edge and excitement to the signal. It’s a kind of “smash and grab” approach that results in crisp, sharp vocals that sit right upfront in the mix. FET compressors are a great choice to help modern vocal styles really “pop” through dense arrangements. The iconic Urei (now Universal Audio) 1176 compressor is the paragon of FET compressors.

The 1176’s input knob also behaves as the threshold control and can be balanced against the output gain control. The attack and release knobs are calibrated opposite of other compressors, with slow values to the left and fast values to the right. The ratio is set via four radio pushbuttons. Most software emulations also include an “all buttons in” setting, a popular trick used on the hardware units as a way of driving the compressor to extreme results. Each ratio setting, including the all-buttons-in setting, has a unique character and vocals typically work well with the attack towards the slowest setting and the release towards the quickest setting. See the chart at the end for more descriptions of FET compressors.

Workflow Strategies – Pre Compression

Regardless of what type of compressor you are using, they are almost always imperfect in one way or another. Imperfection is not a bad thing; it’s a large part of what gives each device its unique flavor. Perhaps their gain reduction is non-linear. Maybe they have attack and release times that change based on the level or frequency content of the input signal. Or maybe a certain amount of saturation or distortion becomes obvious past a specific amount of gain reduction. Once you get to know a compressor, you will usually find that it has a sweet spot— a particular combination of settings that highlight its best tonal and gain-reduction characteristics.

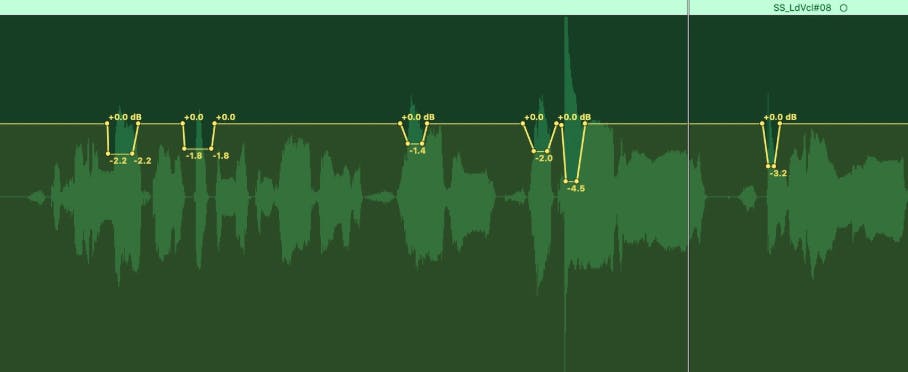

In the real world, the incoming audio level is dynamic and the signal hitting the compressor isn’t consistent. There are loud moments, soft moments and everything in-between. While it is the job of the compressor to take care of these dynamics, if you want a consistent tone from a compressor, it’s a good idea to do a bit of volume automation or clip gain adjustments on your track ahead of the compressor. This pre-compressor leveling will ensure a more even signal is hitting the compressor, allowing it to function in its sweet spot more of the time. The compressor can then uniformly impart its sonic character and easily control the dynamics of the performance. A compressor that constantly jumps in and out of dynamic processing can cause distracting tonal changes in a vocal.

Serial Compression

When working with software compressors, there’s no reason to limit them to just one, or even two, instances on a specific track. Modern vocals that have to compete in dense arrangements can benefit from multiple stages of compression, either in series, parallel, or both. This way, no single compressor has to work too hard. When used judiciously, the result is a vocal with loads of punch and presence that doesn’t sound overly processed.

Using multiple compressors also allows you to take advantage of each one for their unique characteristics. For example, on an aggressive vocal, it can be beneficial to start your vocal chain with a FET compressor. The fast attack time will grab the transients and even out the peaks right off the top. Don’t push it too hard; a few dB of gain reduction with a 4:1 ratio is fine. With the peaks taken care of, insert an opto compressor next to even out the overall level of the signal. Remember, when using multiple stages of compression, just a few dB of gain reduction is all that is needed at any one processing stage.

Working in series like this, you can also insert an EQ between the compressors to enhance, or reduce, the energy of specific frequencies. With the 1176 taking care of the peaks, perhaps a broad gentle boost in the low mids before the LA2A will help bring out the warm area of an otherwise slightly thin female lead. Try a low-pass filter before a compressor to avoid to keep the plosives from triggering hard compression that swallows a word here and there.

Parallel Compression

Another approach to using multiple stages of compression is to run additional compressors along a parallel signal path. For example, start with some natural-sounding compression on your vocal channel for some overall evenness. Then set up a send and instantiate a second compressor with a different character on the aux return channel. The idea is to push this second compressor reasonably hard, and then blend just a little bit of the return channel in with the original.

You might use a Fairchild emulation on the parallel path. Pushed hard, it will grab the transients aggressively. Mixing in just a little of this with the original signal can create a dense, powerful vocal that has enough attack to cut through a pop mix. A VCA with a quick attack is another excellent alternative in this scenario.

With parallel processing, you also have the opportunity to process this return channel with some EQ. Boosting the top end to add some air and presence to the parallel signal is an excellent way of brightening the vocal. Experiment with the order by placing the EQ either before or after the parallel compressor to see which works better.

Vocals As Input To Sidechain Compression

We don’t often think of using a vocal track as a sidechain signal for compressors on instrument tracks, but this can be a great way to tame instruments competing with the vocals.

Let’s say you have a busy rhythm guitar part, a bright synth, or even a tambourine part underneath a female vocalist. This instrument might take up a lot of space in the arrangement and get in the way of the vocal. Set up a bread and butter VCA compressor on the instrument track with a quick attack and quick release. Send the vocal signal into the sidechain input on this compressor and adjust the threshold and ratio so it is clamping down with a few dB or gain reduction. Now, whenever the vocal is competing with the instrument, the compressor will duck the instrument level under the vocal. Sidechain compression is an excellent way of carving out a bit of space when elements of your arrangement compete with each other.

The Simple Modern Approach

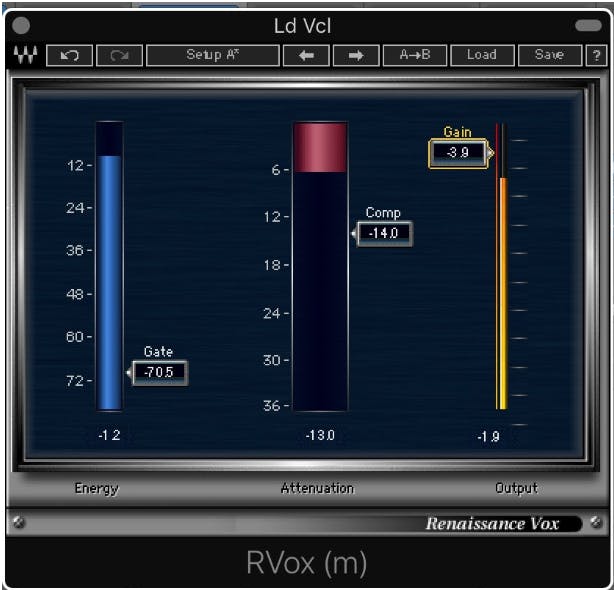

If your head is hurting trying to digest all of these options, fear not. There is an easier way. The beautiful thing about compressor plug-ins is that they don’t always have to be direct emulations of analog hardware. Many software compressors allow you to dial in the amount of compression you want with a single knob or slider, and that’s it! There’s no worrying about the attack and release times, or soft versus hard knees. They are simple to understand and simple to use. RVox from Waves is one such example. Simply pull down the compression slider, adjust to taste, and that’s it. The algorithms are optimized for vocals, and it sounds great for most modern pop music! There’s even an optional gate slider that is effective at reducing unwanted breaths and noise.

With the vast choice of compressor plug-ins available, you will most certainly be able to get your vocals sounding big and warm, or sharp, aggressive and bright – depending on the needs of your track.

To continue learning about the vocals, we recommend reading the following articles: