Distortion is a fickle thing. Distortion is bad in some cases, like when you leave a preamp turned all the way up and accidentally cause a perfect vocal take to clip. In other cases, like a snarling rock guitar solo, distortion can be great. How do you know the difference?

In this blog, we’ll break down everything you need to know about distortion, including different types of distortion, the difference between second and third-order harmonics, and how to use distortion to enhance your mixes.

Good Distortion

When is distortion good? The short answer is; when it’s intentional. But I have a feeling you came here for a little more info than that.

There are many different types of distortion, and while none are inherently good or bad, some are more pleasant-sounding than others. But first, let’s start with what the word distortion actually means.

When speaking about audio, distortion describes any change made to an audio signal. That means everything from amplification to EQ to compression is technically considered distortion.

For our purposes, distortion refers to harmonic distortion, which is the result of clipping, saturation or overdriving a circuit.

Clipping Explained

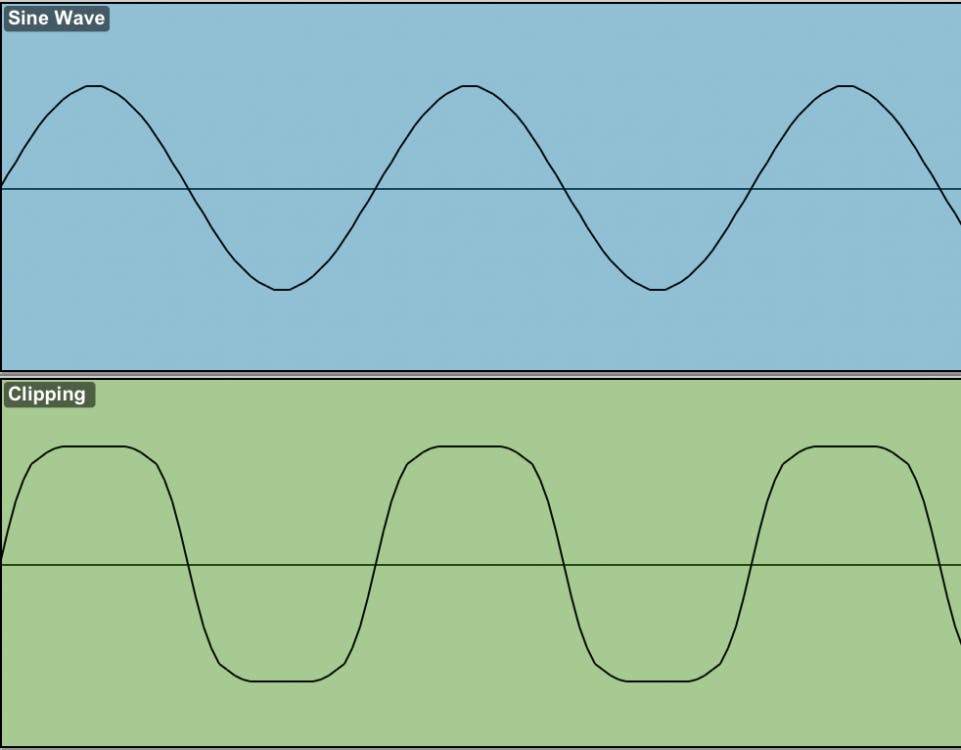

Clipping occurs when the amplitude of an audio signal is turned up so high that the circuit can no longer recreate it. The peaks of the waveform are ‘clipped’ off, causing them to become flat like a square wave. This clipping adds high-frequency overtones to the signal which can make a sound a little fuzzy or even more rich and denser.

Not all circuits clip in the same fashion. Tube circuits and analog tape both produce ‘soft’ clipping when slightly overdriven, which creates a warm tone and gentle compression as the peaks of a signal gradually flatten. Soft-clipping is also commonly referred to as saturation.

On the other hand, transistor-based circuits typically produce a ‘hard’ clipping effect that abruptly flattens peaks for a more aggressive sound. Some transistor circuits are able to emulate the soft-clipping effects of tube designs.

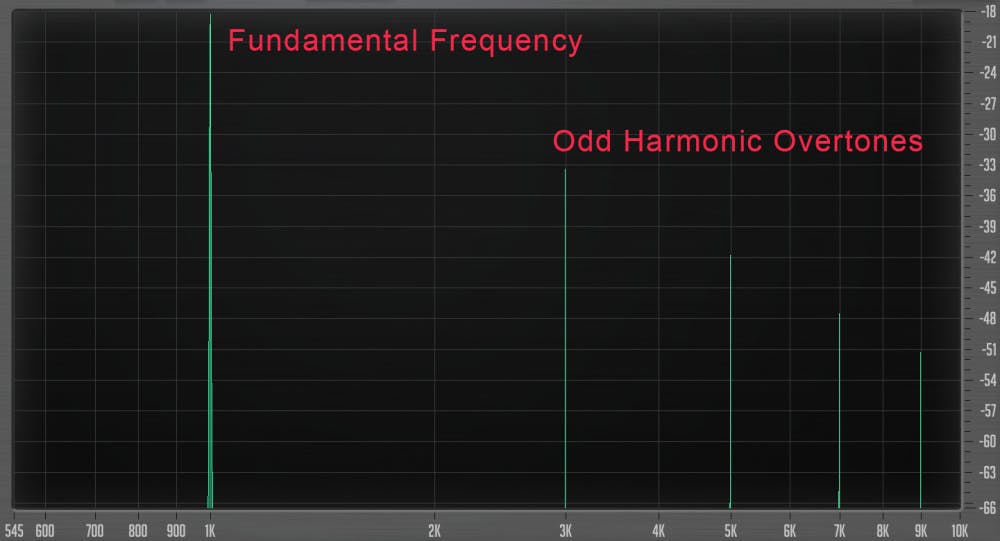

The key difference between hard and soft clipping is the type of harmonic distortion or overtones they produce. Soft clipping yields mostly even harmonics, while hard clipping tends to produce odd harmonic overtones.

It’s also worth noting that clipping in the digital domain creates an entirely different, and generally undesirable sound. Unlike analog systems, digital systems will not let a signal exceed the threshold. Instead, the signal above the threshold is digitally removed from the waveform, which typically results in harsh-sounding, extremely loud harmonic artifacts.

Harmonic Distortion Explained

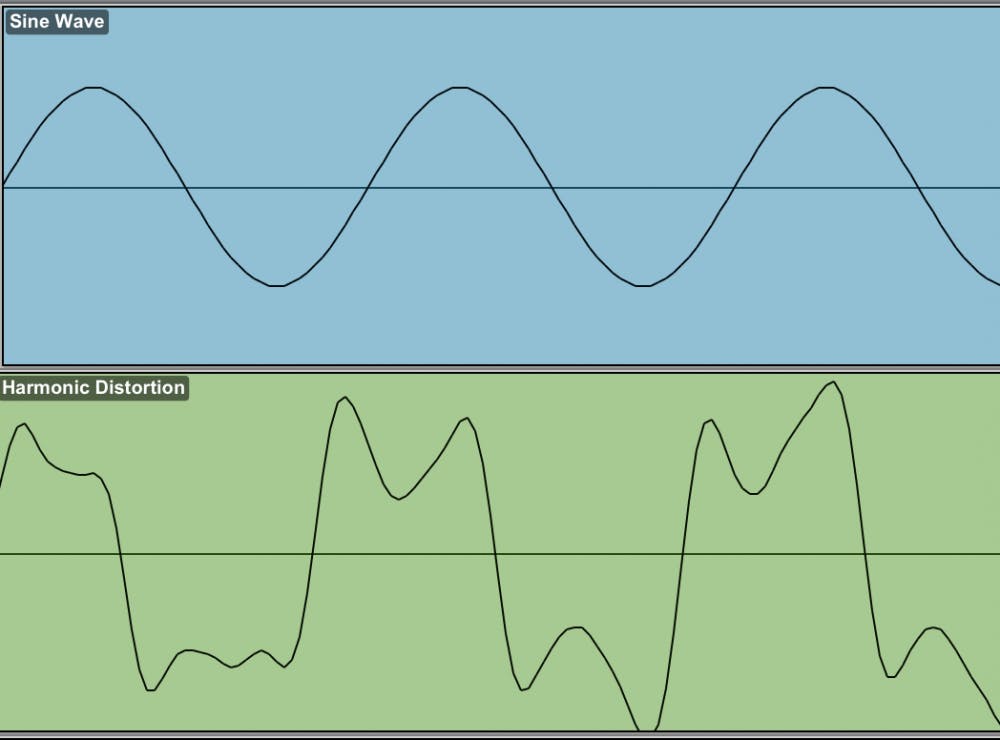

Analog audio circuits can add overtones, or harmonics, to the original signal, creating harmonic distortion. The harmonics may be created by overloading a circuit or as a side-effect of analog tape or tube-, transistor- or transformer-based circuits. Overtones are audio signal created as harmonic multiples of the fundamental frequency in a signal.

Harmonic distortion changes the tone of a sound in a different manner than equalizers. While EQ can increase the amplitude of frequencies that exist in a sound, harmonic distortion adds frequencies that didn’t exist in the original sound. The right amount of these new frequencies can actually enhance the clarity of a sound and bring it forward in a dense mix.

Second-order or ‘even’ harmonics are even-numbered multiples of the fundamental frequencies and create a rich, pleasing sound. Third-order or ‘odd’ harmonics are odd-numbered multiples of the fundamental frequencies, which give the signal an edgier, more aggressive sound.

Generally speaking, tube designs create higher levels of even-order harmonics, while tape and transistor-based designs create higher levels or odd-order harmonics. However, every circuit creates a different blend of both even and odd-order harmonics that give it a unique sound.

Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) is a measurement of how much harmonic distortion a particular circuit is likely to generate. THD calculates the total of both even and odd-order harmonics in a signal and is typically expressed as a percentage.

How to Use Distortion When Mixing

Distortion is one of the most powerful mixing tools at your disposal. It can help fatten up a sound, add sustain, and help tracks cut through a busy mix.

Distortion can come from almost any audio circuit in the signal chain. Oftentimes, it’s not one single use of distortion that makes a track sound full, but the culmination of several layers of subtle and unique-sounding distortion.

Microphones

Loud sounds can lightly saturate tube electronics or cause a tube microphone to clip, introducing distortion at the very beginning of the signal chain. Vintage tube microphones like the Neumann U67 and Telefunken 251 are renowned for their thick, rich tone and it’s these unique saturation characteristics that add dimension to vocals and acoustic instruments.

It’s important to pay close attention when recording with distortion, as you cannot remove it later. Many engineers rely on modeling microphones like the Slate VMS or Townsend Labs Sphere L22 to simulate the sound and feel of tube microphone distortion in the mixing stage.

Preamps

The microphone preamp is the next stage that may introduce distortion. Preamp distortion can be the result of tube or transistor saturation or, as in the case of Neve preamps, transformer-bases saturation, which causes mostly low-frequency harmonic distortion. Some preamps like the SSL VHD designs even feature a built-in distortion control for adding even and odd overtones without actually clipping the signal.

Those of you who are wary of tracking with distortion can use preamp emulation plug-ins like those available from UAD, Slate Digital and Waves to simulate the saturated sound of their favorite tube and solid-state preamps.

Compressors

Another colorful layer of harmonic distortion is typically added using compressors, both on individual tracks and on busses. Compressors inherently change the shape of a waveform, causing distortion. Additionally, compressors are based on circuits that may contain tubes, transistors, and transformers, which each add their own harmonic coloration.

Tube compressors like the Fairchild 670 and Teletronix LA-2A are great for adding soft clipping and transformer saturation distortions to beef up the low mids in your mix.

If you’re looking for a more aggressive sound, try a FET compressor like the UA 1176, or even a colorful VCA compressor like the SSL channel strip compressor. These fast compressors add bright harmonic content and can inject energy into your sounds.

Some compressors like the Empirical Labs Distressor and Fatso also come equipped with distortion and saturation controls for dialing in the perfect amount of smoothness and grit.

Analog Consoles and Summing Mixers

After you’ve got a mix dialed in and you’re ready to print the final version, a bit of saturation can be added by summing tracks on an analog console. Each console offers a slightly different tone—Neve consoles often sound warm and full, API consoles sound bright and airy, and SSL consoles are somewhere in between, with a punchy midrange.

If you work in a small studio, you may not have the room or budget for a large-format analog console, in which case you may want to consider an analog summing mixer. Summing mixers are used to breathe life into sterile-sounding digital mixes by routing multiple audio tracks or stems through analog circuits and summing them to a stereo analog output and back into your DAW.

For those working completely in-the-box, Slate Digital, Waves, Brainworx and Universal Audio make console emulation plug-ins that simulate the unique analog summing characteristics of a number of different consoles. Some plugins even generate different algorithms for each channel to help simulate the experience of working on an actual analog console, where each channel has its own unique sound.

Tape Machines

Another great way to add harmonic distortion to your mix is a tape machine. Analog tape offers a unique sound, unlike any other circuit. The soft-clipping effect combined with odd-order harmonics creates a pleasing compression effect that fattens up the low-end and smooths out edgy high frequencies. Many tape machines also use transformer-based circuits which provide a bit of low-frequency harmonic coloration.

Thankfully, you don’t have to run out and buy a vintage tape machine to apply this treatment to your mix. Several plug-in manufacturers have created emulations of the most popular tape machines, including the Studer A800, J37, and Ampex ATR-102.

Tape machine emulation plug-ins can be applied either directly on a track or on a bus. When applying tape effects directly to individual tracks, try using a two-inch tape setting to simulate the sound of recording to tape. Then apply tape effects to the master bus by using a half-inch setting to simulate the sound of bouncing to a two-track master tape machine. Don’t be afraid to try both if you’re going for a classic sound!

Hardware Distortion Units

There’s one more way to add distortion to your mix—with a proper distortion unit. Some engineers like to use guitar pedals to capture different types of distortion, such as overdrive and fuzz. Some engineers even re-amp signals through literal guitar amps to get the right tone.

SansAmp distortion pedals and rack units have are a studio staple for adding distortion during mixes.

There are even a few analog distortion units specifically designed specifically for mixing. Units like the Thermionic Culture Vulture and the Vertigo Sound VSM-2 deliver versatile controls for dialing in the perfect amount of dirt. Sometimes simply running your digital tracks back through an analog preamp or EQ, like the AMS/Neve 1073SPX can add a certain familiar quality to your sounds.

Plugin Distortion

There are countless quality distortion plug-ins to help your tracks cut through the mix. One of the most popular options is the SoundToys Decapitator, which emulates the distortion characteristics of tape machines, preamps, and even other distortion units. Izotope’s Ozone 9 Exciter emulates the sound of tubes, tape, transformers, and transistors and can be tailored for four different frequency ranges.

Most DAWs even provide a saturation plugin or two. Avid’s own Lo-Fi is a fantastic tool to add a bit of analog grit to drum and bass sounds, while Logic X provides a handful of distortion plugin effects. Kazrog has released True Iron, a plugin that emulates the saturation characteristics of transformers modeled after some legendary gear, like the Neve 1073 and Teletronix LA-2A, among others. Kazrog also produces the SynthWarmer that models 1970’s analog saturation. These and other plugins recreate the sound of analog saturation and distortion and can add dimension and intensity to your digital tracks.

Izotope’s Ozone 9 Exciter allows you to choose between 7 types of distortion, including tape, tubes, transistors and transformers. You can apply any of the exciter types to 4 individual frequency bands.

Now that you have a better understanding of the different types of distortion and how to use them in your mixes. Just remember to use a light touch, as a little distortion can go a long way! As always, make sure you use accurate monitoring so that you can trust what you hear.